UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 Cannot Enhance Taiwan’s International Status

In recent years, UN General Assembly Resolution 2758, passed in 1971, has sparked significant international controversy.

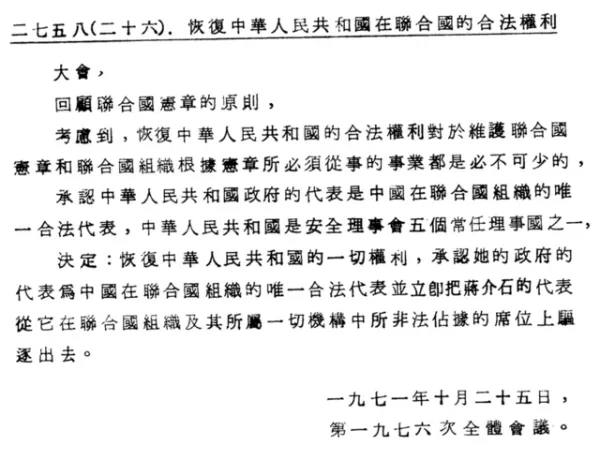

Resolution 2758 is brief. Its full text is as follows:

The General Assembly,

Recalling the principles of the Charter of the United Nations,

Considering that the restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China is essential for the protection of the United Nations Charter and for the cause that the United Nations must carry out under the Charter,

Recognizing that the representatives of the Government of the People’s Republic of China are the only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations and that the People’s Republic of China is one of the five permanent members of the Security Council,

Decides to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.

25 October 1971,

1976th Plenary Meeting.

On May 5, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Taiwan International Solidarity Act. The act explicitly states that UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 recognizes the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the sole legal representative of China in the United Nations but does not address the representation of Taiwan and its people in the UN or any related organizations, nor does it take a position on the relationship between China and Taiwan or include any statement regarding Taiwan’s sovereignty. The act requires U.S. representatives in international organizations to use their voice, vote, and influence to advocate for these organizations to resist China’s attempts to distort resolutions, terminology, policies, or procedures related to Taiwan. It also encourages U.S. allies and partners to counter China’s efforts to undermine Taiwan’s diplomatic relations and partnerships with non-diplomatic countries when appropriate.

In fact, as early as July 25, 2023, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill stating that Resolution 2758 only recognizes the representatives of the PRC as the sole legal representatives of China in the UN, does not address Taiwan’s representation in the UN, and takes no position on the relationship between the PRC and Taiwan or any statement regarding Taiwan’s sovereignty.

Since then, Australia, the Netherlands, the European Parliament, Canada, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the Czech Republic have, through parliamentary motions, official statements, or other forms, explicitly stated that Resolution 2758 does not contain any statements regarding Taiwan’s sovereignty or support interpreting the resolution as establishing the PRC’s sovereignty over Taiwan.

The Chinese government firmly opposes the above interpretations of Resolution 2758 by the U.S. and other countries. The Chinese government states that Resolution 2758 completely resolves the issue of China’s representation in the UN, including Taiwan, and clearly states that there are no “two Chinas” or “one China, one Taiwan.” It asserts that “as an inseparable part of Chinese territory, Taiwan has no basis, reason, or right to participate in the United Nations or other international organizations limited to sovereign states. On this matter of principle, there is no gray area or room for ambiguity.”

The two interpretations are diametrically opposed. Which is correct?

To be fair, based on the original intent of Resolution 2758, the Chinese government’s interpretation is correct; based on the text of the resolution, the U.S. interpretation is also reasonable.

Let us review the historical background and process of Resolution 2758.

The Republic of China (ROC) was originally a founding member of the United Nations and one of the five permanent members of the Security Council. In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seized control of the mainland and established the People’s Republic of China, but it did not immediately enter the UN. The ROC government, having retreated to Taiwan, retained its UN seat and permanent membership in the Security Council. This led to a prolonged struggle between the two sides over the UN seat. Both sides insisted that there was only one China and that they were the sole legitimate representative of China, adopting a “you or me, but not both” stance, akin to “Han and thief cannot coexist.” This put the UN in a difficult position.

Initially, Western countries led by the U.S. supported Taiwan and opposed the CCP regime. However, over time, they increasingly viewed it as unrealistic and inappropriate to exclude the CCP regime, which controlled the entire mainland, from the UN while allowing the Nationalist government, which controlled only Taiwan, to continue representing all of China. At the same time, they believed that the CCP should not be allowed to “liberate” Taiwan by force. As a result, several Western countries proposed allowing the PRC to enter the UN and become a permanent member of the Security Council while retaining the ROC’s membership status, or allowing the people of Taiwan to hold a referendum to decide whether Taiwan should merge with the PRC, become independent, or be placed under UN trusteeship. If either Taiwan or the mainland had been willing to accept such an arrangement, these proposals might have been feasible. However, at the time, both the Taiwan government and the mainland government firmly opposed these arrangements, causing the Western proposals to fail.

From 1950 to 1970, during several UN General Assembly meetings, the Soviet Union and other countries proposed restoring the PRC’s seat in the UN. Initially, the U.S. and its allies excluded these proposals from the agenda under the pretext of “postponement of consideration.” Later, they argued that the issue of China’s representation was a “major issue” requiring a two-thirds majority in the General Assembly, thus rejecting the proposals. However, by 1970, the situation had changed, with more countries supporting the PRC’s representation. Additionally, a series of African, Asian, and Latin American countries joined the UN, most of which supported the PRC’s representation. At the UN General Assembly, the votes in favor of the PRC’s representation (51 votes) surpassed the opposing votes (49 votes) for the first time, though the proposal did not pass because it did not meet the two-thirds majority required for major issues. It became increasingly difficult for the U.S. and others to block the PRC. By 1971, the evolving international situation further favored Beijing. At the 26th General Assembly that year, Albania and other countries again proposed restoring the PRC’s representation in the UN, including its role as a permanent member of the Security Council, and expelling Taiwan. At that time, the PRC had gained widespread support within the UN, and the U.S. estimated that it could no longer block the PRC’s entry. Thus, after consultations with the Taiwan authorities, the U.S. changed its strategy, aiming for “dual representation,” hoping to allow the PRC to enter the UN and take the Security Council seat while preserving the ROC’s membership in the General Assembly. According to retired Taiwanese diplomat Lu Yizheng in his memoir No Power to Turn Back the Heavens, “after multiple secret consultations between the U.S. and Taiwan, President Chiang Kai-shek reluctantly agreed at the last moment.”

After obtaining Chiang Kai-shek’s consent, the U.S. proposed a temporary motion to divide the Albanian proposal into two parts: first voting on whether to admit Beijing, then voting on whether to expel Taiwan. The U.S. estimated that since not all countries supporting Beijing’s admission also supported expelling Taiwan, this might preserve Taiwan’s seat. However, the U.S. motion was rejected. Taiwan’s representatives, realizing defeat was inevitable, requested to speak on procedural grounds, announced their withdrawal from the UN, and left the meeting hall. Subsequently, the Albanian proposal was passed in its entirety. From then on, Beijing took the place previously occupied by Taiwan, and Taiwan was forced to leave the UN.

Reviewing the background and process of Resolution 2758, it is clear that the intent of the Albanian and other countries’ proposal was to replace the ROC government, which ruled Taiwan, with the PRC government, which ruled the mainland, as the occupant of China’s seat in the UN. This indicates that the Chinese government’s interpretation of Resolution 2758 is correct. However, due to their non-recognition and disdain for the ROC government, the Albanian proposal referred to it as “Chiang Kai-shek’s representatives,” without mentioning “Republic of China” or “Taiwan.” This left room for the new interpretation by the U.S. and other countries, making their interpretation reasonable as well. As Ming Juzheng, an honorary professor at National Taiwan University and an expert on cross-strait issues, said: “The CCP was too clever by half, creating a loophole. By referring to the expulsion of Chiang Kai-shek’s representatives, the CCP never imagined that their word games back then would give others interpretive space today. If they had referred to expelling the representatives of the Republic of China or the Republic of China (Taiwan), Taiwan might have been completely doomed today.” (https://www.tiktok.com/@alanwei9/video/7274169414604360966)

The U.S. proposed a new interpretation of Resolution 2758 to promote Taiwan’s representation in the UN and its related organizations.

Take the World Health Assembly (WHA) as an example. During Ma Ying-jeou’s presidency, because he recognized the 1992 Consensus, Taiwan participated in the WHA as an observer under the name “Chinese Taipei.” After Tsai Ing-wen took office, due to her refusal to recognize the 1992 Consensus, Taiwan was excluded from the WHA by China. In recent years, the number of countries supporting Taiwan’s participation in the WHA has increased. For instance, at last year’s WHA, Taiwan’s allies proposed a motion to “invite Taiwan to participate as an observer,” and 26 member states and the EU, as an observer, publicly spoke in support of Taiwan, 15 more than in 2023. U.S. officials emphasized that UN Resolution 2758 does not preclude Taiwan from meaningful participation in the UN system and other multilateral forums. Per procedure, the assembly arranged for two rounds of two-on-two public debates between representatives of both sides, after which the assembly chair ruled to once again reject including Taiwan’s allies’ proposal on the agenda, excluding Taiwan from the WHA. With this year’s WHA approaching, it is estimated that the number of countries supporting Taiwan’s participation may increase slightly, but it will still be insufficient to secure Taiwan’s entry into the WHA.

Despite the U.S.’s new interpretation of Resolution 2758, among the UN’s 193 member states, far fewer countries support the U.S. interpretation than support China’s. A survey published on January 15 this year by the Australian think tank Lowy Institute shows that only 40 countries (21%) adhere to a “One China policy,” recognizing the PRC as the sole legitimate government representing China but not supporting the claim that “Taiwan is part of China.” In contrast, 142 countries (74%) support Beijing’s sovereignty claims over Taiwan, with 119 (62%) recognizing China’s “One China principle” and 95 (49%) supporting the PRC’s “national reunification.” An analysis published by The Economist in February this year noted that 70 countries have publicly stated support for China’s unification of Taiwan “by any means,” including military means. This indicates that it is nearly impossible for the U.S. and other countries to use their new interpretation of Resolution 2758 to secure Taiwan’s rightful international status. The U.S. cannot even secure Taiwan’s participation as an observer in the WHA, let alone bring Taiwan into the UN.

Looking back at the U.S.’s new interpretation of Resolution 2758, while it is reasonable based on the text, it appears weak. First, the U.S. only proposed a different interpretation and made a big deal of it fifty years after Resolution 2758, without previously objecting to China’s interpretation. This itself undermines its persuasiveness. Second, since the U.S. claims that Resolution 2758 does not take a position on the relationship between the PRC and Taiwan or include any statement on Taiwan’s sovereignty—meaning a country could establish formal diplomatic relations with both the PRC and Taiwan—why doesn’t the U.S. take the lead in establishing diplomatic relations with Taiwan?

We all remember that at the 1971 UN General Assembly, the U.S. proposed dividing the Albanian proposal into two parts: first voting on admitting Beijing, then voting on expelling Taiwan. This shows that the U.S. originally intended to accept Beijing while retaining Taiwan. However, when the U.S. established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1979, it simultaneously severed ties with the ROC. This is the key reason for the U.S.’s current awkward position on cross-strait issues. A few days ago, President Trump expressed complaints, saying that the worst thing Nixon did was to bring the U.S. into contact with China. Trump’s criticism may refer to establishing diplomatic relations with China, but it could also refer to severing ties with Taiwan. Establishing ties with China is one thing, but why sever ties with Taiwan at the same time?

In his memoir, Lu Yizheng wrote that on the eve of U.S.-PRC diplomatic normalization in 1977, he took the initiative to privately probe the U.S. side on whether it was possible to adopt the two-Germanies model, recognizing both the PRC and the ROC. The U.S. side indicated it was impossible. President Carter’s East Asia advisor, Oksenberg, said that Carter had already expressed support for the Shanghai Communiqué (signed by Nixon, which noted that the U.S. acknowledges that both sides of the Taiwan Strait believe there is only one China) and could not change it. Oksenberg also quipped, “A zero-based budgeting system might work, but a zero-based foreign policy is too absurd.” This meant that if Taiwan had agreed earlier to let the U.S. adopt the two-Germanies model, it might have been feasible, but Taiwan had consistently refused. Now, asking the U.S. to start over and recognize both the mainland and Taiwan was too late and unfeasible.

All of this indicates that it lacks practical feasibility for the U.S. and other countries to use their new interpretation of Resolution 2758 to secure Taiwan’s rightful international status.

The only way to secure Taiwan’s rightful international status is for the U.S. and other countries to directly establish (or restore) formal diplomatic relations with the Republic of China. This does not rely on a new interpretation of Resolution 2758 to address cross-strait relations but instead adopts the “one country, two governments” model, i.e., the Korean model. Alternatively, even if the U.S. and other countries establish formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan based on their new interpretation of Resolution 2758, it still would not constitute “two Chinas” or “one China, one Taiwan.” It would not indicate that Taiwan and the mainland are two separate countries. One defining feature of a state is its territory, and two separate states should have distinct territories. However, according to the constitutions of both the PRC and the ROC, both the mainland and Taiwan are considered part of their respective territories, meaning the territories of the PRC and the ROC overlap rather than being separate. Thus, they are one country, not two. Unless Taiwan amends its constitution to remove the provision that “the mainland is part of the ROC’s territory,” its relationship with the PRC would constitute two countries, i.e., “two Chinas.” Furthermore, unless Taiwan also changes its name to the Republic of Taiwan, its relationship with the PRC would constitute “one China, one Taiwan.” Since Taiwan has neither amended its constitution nor changed its name, the relationship between Taiwan and the mainland—i.e., between the ROC and the PRC—is not a state-to-state relationship, not “two Chinas,” nor “one China, one Taiwan,” but rather, and only, a relationship of “one country, two governments” or “one China, two governments.”

I have consistently advocated for the U.S. to establish diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Two years ago, I co-authored an article with Perry Link, emeritus professor at Princeton University, published in The Wall Street Journal (English link: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-korean-model-for-taiwan-one-country-two-governments-communique-china-ccp-beijing-strategic-ambiguity-c12270fa?st=2jojdkoegyyhn4m). The Chinese translation is as follows:

In the 1990s, even Beijing abandoned its rejection of the “one country, two governments” formulation.

Hu Ping, Perry Link (March 29, 2023)

Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen is visiting the U.S., but under the peculiar diplomatic protocol governing U.S.-Taiwan relations, she is not on a state visit or even a visit. Officials at the State Department and the White House are at pains to refer to it as a “transit.”

When Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger negotiated the 1972 Sino-U.S. Joint Communiqué in Shanghai, Taiwan’s status was the most difficult issue. Beijing made some hard demands, which the American side neither accepted nor challenged, leaving room for “strategic ambiguity” in its support for Taiwan after the U.S. formally established relations with Beijing and broke with Taipei in 1979.

This approach may have been wise at the time, but a clear statement from the U.S. on the legitimacy of the Taiwan government would now be more conducive to stability. The U.S. could recognize Taipei under the principle of “one country, two governments.” This would not support Taiwan’s independence or negate the “one China” principle that the Chinese government has upheld since 1972. Instead, it would follow the evolution of Beijing’s own approach to dealing with Taipei.

In the Shanghai Communiqué, in addition to opposing “one China, one Taiwan,” “two Chinas,” and “Taiwan independence,” the Chinese side also explicitly opposed “one China, two governments.” Until the mid-1990s, the Chinese Communist Party’s position remained unchanged, but then subtle shifts began to emerge.

In a January 1995 speech, President Jiang Zemin stated his firm opposition to “two Chinas” and “one China, one Taiwan” but made no mention of “one China, two governments.” The 1993 Chinese white paper on the Taiwan issue stated that China rejected the “two-Germanies” and “two-Koreas” solutions to the Taiwan issue, but the 2000 white paper continued to oppose the two-Germanies model while making no mention of opposing the two-Koreas model. Since then, “one China, two governments” and “two Koreas” have systematically Ascending systematic ally disappeared from official speeches and documents. On a sensitive topic like Taiwan, these subtle changes cannot be accidental. What do they mean?

The German and Korean models are different. The 1974 East German constitution regarded East Germany as a separate state from West Germany. In contrast, the constitutions of North and South Korea both regard their governments as part of a unified Korean homeland. This is the “one country, two governments” concept that Beijing removed from its “firmly opposed” list in the late 1990s.

For Taiwan, the “two-Koreas solution” would be a significant step forward. North and South Korea both allow each other to establish diplomatic relations with foreign countries, join the United Nations and other international organizations, and participate as separate teams in the Olympics and World Cup. Since 1992, Beijing has maintained diplomatic relations with both Pyongyang and Seoul.

Of course, both sides of the Taiwan Strait would object. Some Taiwanese do not want to live under a “second” Chinese government because they do not consider themselves Chinese at all. But even for them, it would be hard to reject a “one country, two governments” arrangement, as it would fundamentally reduce the dire threat they face from Beijing.

The Beijing regime has obvious reasons to insist on the illegitimacy of the Taipei regime. Taiwan is a vibrant democracy with the world’s 21st-largest economy, but for the Chinese Communist Party, it is an embarrassing counterexample to the claim that democracy is incompatible with Chinese culture. “Unifying the motherland” is critical to the Communist Party’s efforts to stoke nationalism and enhance its legitimacy.

However, as practical needs have changed, Beijing has also changed. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Beijing and Taipei regimes accused each other of being illegitimate governments; commercial and people-to-people exchanges across the strait were virtually nonexistent. But starting in the 1980s, increasing in the 1990s, and burgeoning in the 2000s, cross-strait exchanges flourished, and the need to address issues collaboratively grew. The two sides signed over 20 agreements on investment, trade, people-to-people exchanges, crime-fighting, and other matters.

Such agreements are typically signed by governments, so cross-strait negotiations inevitably raised a tricky question: how to sign agreements while pretending not to. Like U.S.-Taiwan relations, the answer was for both sides to establish a non-governmental organization. On the mainland, the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits was established; in Taiwan, the Straits Exchange Foundation was created. In Chinese, these organizations are called “white gloves,” but everyone knows whose hands are at work.

In practice, “one country, two governments” is already in place. In 2005 and 2011, mainland Chinese think-tank scholars openly proposed this without facing punishment.

In 2015, Xi Jinping himself did so. He agreed to meet Taiwan’s President Ma Ying-jeou in person on nominally equal terms. The two met in Singapore as “Leader of Taiwan” and “Leader of Mainland China.” Both set aside official titles, addressing each other as “Mr.” (xiansheng). Mr. Xi’s agreement to these terms indicates it was his initiative. No one could have forced him. (Mr. Ma Ying-jeou this week became the first former Taiwan president to visit the mainland.)

Beijing will surely condemn a U.S. move to recognize Taiwan; it will not miss an opportunity to boost its prestige by stoking nationalism. But beneath the surface, a calmer response may lie. It is hard to imagine that Beijing’s strategists did not anticipate the world’s reaction to its gradual shift in Taiwan policy. In practice, this change would not alter the status quo but merely acknowledge it.

On the issue of U.S.-Taiwan diplomatic relations, the author has previously published the following articles:

“U.S.-Taiwan Diplomatic Relations: The Time Is Now” (May 15, 2019, link: https://www.upmedia.mg/news_info.php?Type=2&SerialNo=63154).

“Why the CCP No Longer Opposes ‘One Country, Two Governments’” (April 17, 2020, link: https://www.chinesepen.org/blog/archives/148614).

Full text link: (https://yibaochina.com/?p=255775)

[This article was first published by Yibao China. When reprinting, please include the source and link: https://yibaochina.com/?p=255775]

[The author’s views do not represent the stance of this publication.]